(From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

The I Ching (Wade-Giles) or “Yì Jīng” (pinyin), also known as the Classic of Changes, Book of Changes and Zhouyi, is one of the oldest of the Chinese classic texts. The book contains a divination system comparable to Western geomancy or the West African Ifá system; in Western cultures and modern East Asia, it is still widely used for this purpose.

Traditionally, the I Ching and its hexagrams were thought to pre-date recorded history, and based on traditional Chinese accounts, its origins trace back to the 3rd to the 2nd millennium BC. Modern scholarship suggests that the earliest layer of the text may date from the end of the 2nd millennium BC, but place doubts on the mythological aspects in the traditional accounts. Some consider the I Ching’ as the oldest extant book of divination, dating from 1,000 BC and before. The oldest manuscript that has been found, albeit incomplete, dates back to the Warring States Period (around 475–221 BC).

During the Warring States Period, the text was re-interpreted as a system of cosmology and philosophy that subsequently became intrinsic to Chinese culture. It centered on the ideas of the dynamic balance of opposites, the evolution of events as a process, and acceptance of the inevitability of change.

The standard text originated from the ancient text (古文經) transmitted by Fei Zhi (费直, c. 50 BC-10 AD) of the Han Dynasty. During the Han Dynasty this version competed with the bowdlerised new text (今文經) version transmitted by Tian He at the beginning of the Western Han. However, by the time of the Tang Dynasty the ancient text version, which survived Qin’s book-burning by being preserved amongst the peasantry, became the accepted norm among Chinese scholars.

History

Traditional view

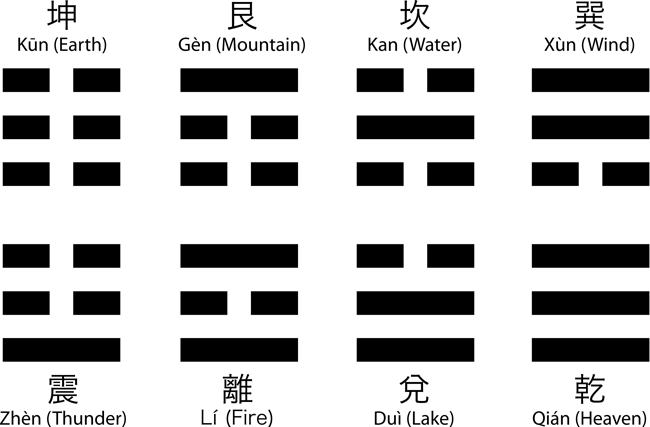

Traditionally it was believed that the principles of the I Ching originated with the mythical Fu Xi (伏羲 Fú Xī). In this respect he is seen as an early culture hero, one of the earliest legendary rulers of China (traditional dates 2800 BC-2737 BC), reputed to have had the 8 trigrams (八卦 bā guà) revealed to him supernaturally. By the time of the legendary Yu (禹 Yǔ) 2194 BC – 2149 BC, the trigrams had supposedly been developed into 64 hexagrams (六十四卦 lìu shí sì gùa), which were recorded in the scripture Lian Shan (《連山》 Lián Shān; also called Lian Shan Yi). Lian Shan, meaning “continuous mountains” in Chinese, begins with the hexagram Bound (艮 gèn), which depicts a mountain (¦¦|) mounting on another and is believed to be the origin of the scripture’s name.

After the traditionally recorded Xia Dynasty was overthrown by the Shang Dynasty, the hexagrams are said to have been re-deduced to form Gui Cang (《歸藏》 Gūi Cáng; also called Gui Cang Yi), and the hexagram responding (坤 kūn) became the first hexagram. Gui Cang may be literally translated into “return and be contained”, which refers to earth as the first hexagram itself indicates. At the time of Shang’s last king, Zhou Wang, King Wen of Zhou is said to have deduced the hexagram and discovered that the hexagrams beginning with Initiating (乾 qián) revealed the rise of Zhou. He then gave each hexagram a description regarding its own nature, thus Gua Ci (卦辭 guà cí, “Explanation of Hexagrams”).

When King Wu of Zhou, son of King Wen, toppled the Shang Dynasty, his brother Zhou Gong Dan is said to have created Yao Ci (爻辭 yáo cí, “Explanation of Horizontal Lines”) to clarify the significance of each horizontal line in each hexagram. It was not until then that the whole context of I Ching was understood. Its philosophy heavily influenced the literature and government administration of the Zhou Dynasty (1122 BC-256 BC).

Later, during the time of Spring and Autumn Period (722 BC-481 BC), Confucius is traditionally said to have written the Shi Yi (十翼 shí yì, “Ten Wings”), a group of commentaries on the I Ching. By the time of Han Wu Di (漢武帝 Hàn Wǔ Dì) of the Western Han Dynasty (c. 200 BC), Shi Yi was often called Yi Zhuan (易傳 yì zhùan, “Commentary on the I Ching”). Together with the commentaries by Confucius, I Ching is also often referred to as Zhou Yi (周易 zhōu yì, “Changes of Zhou”). All later texts about Zhou Yi were explanations only, due to the classic’s deep meaning.

Modernist view

In the past 50 years a “Modernist” history of the I Ching emerged based on research into Shang and Zhou dynasties’ oracle bones, Zhou bronze inscriptions and other sources (Marshall 2001, Rutt 1996, Shaughnessy 1993, Smith 2008). In the 1970s, Chinese archaeologists discovered intact Han dynasty-era tombs in Mawangdui near Changsha, Hunan province. One of the tombs contained the Mawangdui Silk Texts, a 2nd century BC new text version of the I Ching, the Dao De Jing and other works, which are mostly similar yet in some ways diverge from the received, or traditional texts preserved historically. This version of the I Ching, despite its textual form, belongs to the same textual tradition as the standard text, which suggests it was prepared from an old text version for the use of its Han patron.

Rather than being the work of one or several legendary or historical figures, the core divinatory text is now thought to be an accretion of Western Zhou divinatory concepts. According to Daniel Woolf, the text reached a “definitive form” at the end of the 2nd millennium BC.As for the Shi Yi commentaries traditionally attributed to Confucius, scholars from the time of the 11th century AD scholar Ouyang Xiu onward have doubted this, based on textual analysis, and modern scholars date most of them to the Warring States period (475 BC-256 or 221 BC), with some sections perhaps being as late as the Western Han period (206 BC-9 AD).